MA Thesis with Distinction | 2018 | Architectural Association

“The wheel is an extension of the foot; the book is an extension of the eye; clothing an extension of the skin; electric circuitry, an extension of the central nervous system. ”

The central premise of the thesis is that the objects humans fabricate and use can be understood as extensions of the ones using them. In order to investigate this claim, the thesis focuses on three theoretical foundations. The first is the discourse of Technics, which posits tools and language as the result of a human tendency to ‘exteriorize’. Through exteriorization these objects become a form of memory and as such hold an important role in human evolution. The second is the existential analytic of the German philosopher Martin Heidegger. Through his tool analysis, this chapter investigates the interaction of humans with tools and consequently with the world. Lastly, through the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben and his theory of ‘use’, the thesis investigates how this interaction with the world enfolds through use of ourselves and the objects around us. It is through use of things, that we constitute who we are.

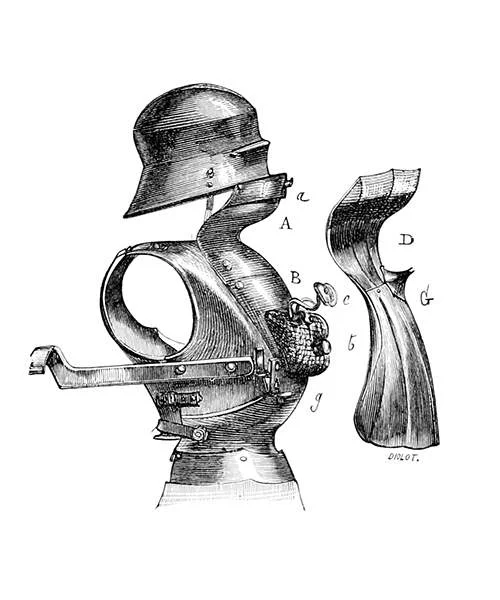

In architectural terms the consequences of such an investigation are twofold. Firstly, it proposes an intrinsically relational approach to architecture, where architectural objects are understood as extensions of the people using them. Secondly, as in the case of tools, buildings and rooms are not just objects used by subjects, but they constitute each other through use. The thesis incorporates a number of objects in an intentionally isolated manner, but still bound by the body of the thesis; hammers, ships, armor, pieces of machinery, sculptures and trinkets – invoking a feeling one would get as if entering a Cabinet of Curiosities. Through tools, everyday objects, human bodies, language and technology, the aim is to unfold the story of architecture indirectly. Along the way it attempts to understand the mechanisms behind the human interaction with the world through habits, rituals, use and appropriation.

Thesis excerpt: The Extended Self

In his book The Medium is the Massage, media theorist Marshal McLuhan proposes the idea that human artifacts are to be understood as extensions of the human body and brain. The idea that the objects we produce are extensions of ourselves has greater consequences than those objects just expanding our capacity to act and being in some way a part of us – it is an idea at the heart of anthropogenesis, of what makes us human in the way we are. Such an idea has the potential to explore what is the relationship between ourselves, our bodies and technology, in the wide sense of that term that we will soon define, as well as how we transform and inhabit our environment. Extending the self implies that ‘self’ is more akin to a field than a singular static unit; a field of being comprised of objects and places as well as others, with the body at its center. It is characterized by its ability of extension into physical and cultural environments. This phenomenon becomes most evident in use of human fabricated objects and tools, but indeed it can be applied to the way we handle language, our bodies and others. For instance, while we rely on a tool to accomplish a specific task, this tool is not handled as an external object. Instead, we “pour ourselves into it and assimilate it as a part of ourselves”.

The importance of the human body comes into the foreground. Sharing the same physiological and sensory apparatus – the human body; allows us to identify with others, by analogical extension of our own bodies and the way they shape our experience of the world in the fashion that is inconceivable if we were all built differently. Even considering the obvious distinctions between all human beings, the common denominator of the body makes it possible not to see others as objects, but to understand and empathize with them on an embodied level. By understanding human artifacts as extensions of the self, it can offer a broader theoretical ground on how to understand architecture, through the making and use of its objects – which include buildings, the objects inside those buildings and the wider context in which they are located it. The thesis has three main theoretical influences. First it is the discourse of technics, by the French philosopher Bernard Stiegler and the anthropologist Andre Leroi-Gourhan, to explore the relationship of humans and tools in a co-evolutionary sense and what it means to externalize. Their work establishes the importance of the objects humans fabricate. Second, it is the existential analytic of the German philosopher Martin Heidegger.

Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire raisonné du mobilier français de l'époque carlovingienne à la Renaissance, vol. 2, 1858–1870

“While we rely on a tool or a probe, these instrument are not handled as external objects. Instead, we pour ourselves into them and assimilate them as part of ourselves.”

Through his analysis of the tool and what he calls being present-at-hand as opposed to ready-to-hand, the thesis attempts to understand how the human interaction with those objects occurs. This offers an insight into how we interact with the world around us. While his writings on dwelling have been extensively referred to in architectural theory, his writings on tools and equipment can offer us a fresh insight into the transformation and inhabitation of our built environment. Lastly, with the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben we will explore how through the use of the world we constitute who we are, by using we appropriate. All of these theories are already intrinsically interconnected, the cross-fertilization of ideas happening within the authors themselves. This thesis will combine them into what can be called a theory of the extended self. Along the way it will attempt to narrate the story of architecture indirectly, through tools, objects, the human body and technology.