Versions of the Critic | 2018 | Architectural Association, London

Yves Klein

Blue Monochrome

1961

Can a judgement of taste be based on universal criteria that go beyond the subjective opinion? Through his Critique of Judgement, Immanuel Kant gives us his account of what beautyl is and what constitutes an aesthetic judgement as a part of human cognition. Indeed he does place beauty as a product of the mind instead of an inherent property of an object, but he also makes a claim to its inter-subjective universality and states that we experience free beauty only as disinterested pleasure. For Kant, aesthetic judgement holds an equal position to the other faculties that he establishes in his analytic approach to the human mind. The essay tries to explore his definition of beauty and his claim to its universality, under the immediate context of his notion of judgement and the wider context of his system of Categories, while briefly touching upon his other judgements; the agreeable, the good and the sublime.

Before Understanding Kant’s aesthetics it is necessary to refer to his theory of how the human mind works in general. Called the Copernican revolution in philosophy, his transcendental idealism tries to synthesize the previous discrepancies of empiricism and rationalism. Kant distinguishes reality between phenomena- the appearances of objects that we grasp through our understanding; and the noumena- things in themselves that we cannot grasp. Subsequently objects we intuit in space and time are merely appearances , representations and not objects that exist independently of our intuition and that we know nothing of substance about the things in themselves of which they are appearances. Since Kant is an idealist he does believe that the human mind is actively constructing reality – this process being based both on empirical knowledge, but also before it. A priori knowledge is derived from reason alone, its truth independent from empirical evidence, such as in the case of mathematics, tautologies and deductions. The truth in a posteriori knowledge on the other hand is dependent on experience and empirical evidence, an empirical fact unprovable by reason alone, such as in science. The transcendental subject according to Kant consists of both a priori and a posteriori laws, constructing reality through a harmonizing process of the faculties of the mind.

In his theory of the mind, Kant ascribes three main faculties to the mind as a whole; cognition, the feeling of pleasure and displeasure, and desire. In addition, the three cognitive faculties of the mind for him are the Understanding, Judgement and Reason. In his previous critiques he ascertains that a priori principles of Understanding are responsible for empirical knowledge and the principles of Reason for desire. In his Critique of Judgment he is trying to find which a priori principles are assigned to Judgement and feeling. [1] According to Kant, the broader definition of Judgement would be that it is a specific kind of cognition, defined as any conscious mental representation of an object. It is a spontaneous and innate cognitive capacity. Furthermore, in this context he equals the faculty of judging to the faculty of thinking. [2] More specifically, judgment for Kant is the faculty of thinking the particular as being contained in the universal”. [3] If we already have the universal, such as a principle or a rule, the judgement about a particular under this universal is determinant. But if only the particular is given and the judgement must be made to find the universal, we are talking about reflective judgement. He concludes that reflective judgement has an a priori principle related to feeling in the same way that the a priori principles of understating are related to our knowledge of empirical facts and the principles of practical reason to desire.

The four possible reflective judgements for Kant are the agreeable, the good, the beautiful and the sublime. The agreeable would be the judgements based only on sensory input and because of this they are purely subjective. On the other hand judgments of the good are made on ethical principles. Since Kant is a deontologist his ethics are based on a supreme principle of moral law, which is fixed on the absolute notion of reason. Therefore according to Kant things are either moral or they are not and in this sense a reflective judgement of the good should be purely objective, in a way the opposite to the agreeable and its subjectivity. He distinguishes beauty from pleasure by explaining that pleasure is an interested emotion that seeks gratification from the object; the beautiful is purely disinterested, it seeks nothing from the object and makes no demands. The point of the beautiful is not to possess the object, hence a beautiful object doesn’t even need to be real, it can be imaginative. In the judgement of the beautiful, the pleasurable comes after the judgement, otherwise it couldn’t be universal. When distinguishing the beautiful from the good, according to Kant the good seeks beauty as a means to a higher end, whereas the beautiful accepts it unconditionally as a finished thing in itself. For instance when observing a painting, the good would inquire in to the moral implications of the painting, in other words its purpose; but if observed aesthetically the painting is an end in itself, without its moral purpose. When talking about the beautiful and the sublime, for Kant they are also different from the rest of the judgements because they are what he defines as subjective universals. Before him, Burke also had this notion of subjective universality and his reasoning for it was that taste and imagination are based on the senses and since the senses are universal, taste is also universal. Kant on the other hand states that what allows the subjective to be universal is exactly its subjectivity - by not being dependant on any ulterior ends. Since the beautiful is not based on concepts, it is free and also indifferent even to the existence of the object; because of this we feel it without any restraints or prejudice and therefore, according to Kant, we all ought to feel it in the same way. It is universal because it is free from all agendas and ideologies, for anyone that observes it disinterestedly. The most obvious critical response to this notion is how can something be observed in an absolute disinterested way, especially in the context of modern philosophy that puts such an emphasis on the individual being under the constant influence of various ideologies.

Kant is also concerned how to draw a connection between the laws of nature and moral freedom, which is also crucial to his theory of aesthetic taste. He tries to prove that the a priori principle of reflective Judgement establishes a harmony between nature and freedom. Körner in his book notes that such a principle would have to be synthetic and also a priory, logically independent of any proposition which describes sense-impressions. [4] By synthesis, Kant implies an act of combining intuitions and concepts, intuitions beings the representations of objects that are given to us through sensibility, they form the starting point for all cognition. As he states in the Critique of Pure reason, “By synthesis, in its most general sense, I understand the act of putting different representations together, and of grasping what is manifold in them in one knowledge.” [5] To summarize, if Judgement is thinking of the particular as contained in the universal, then reflective Judgement is the faculty of searching for the universal when the particular is given. Kant tries to find these a priori laws of reflective judgement by their function in science. He claims that these laws are either synthetic a priori conditions of scientific knowledge and are discoverable, or they must be a posteriori laws, empirical propositions which can be discovered only through experiment and observation. [6] In order to conduct a reflective judgement Kant needs the principle of harmony between nature and our mental capacities, in other words in order for us to be able to grasp the natural laws, nature needs a principle of purposiveness. This principle “consists in finding for the particular which is presented in perception the universal; and in finding different such universals a connection in a unity of principle”. [7] What Kant tries to claim is that the condition for us to be able to make cognitive and aesthetic judgements about the world is that the world itself is designed to fit the human cognition. When he is talking about purpose, he is concerned with purpose in a metaphysical sense, a final cause that involves the purposive whole and a purpose achieved by it, but most importantly without human desire. In other words, an object is purposive if it appears to be designed, made with a purpose. By this Kant does not imply that nature is an intelligent being, or that there is a being placed above nature. He states that “our only intention is to designate a kind of natural causality in an analogy with our own causality in the employment of reason, for the purpose of keeping in view the rule upon which certain natural products are to be investigated. [8] What is characteristic for an object of aesthetic judgment is that it is purposive without purpose. [9] To clarify, aesthetic judgement being purposive without a purpose means that it takes the same form as cognitive judgement, but doesn’t subsume the object under a concept. Cognitive judgement aims to identify an object in the world to a specific concept. For instance when we perceive a dog, we identify it with the concept that we have of what a dog is, this concept according to Kant is the objects purpose. Therefore cognitive judgement is a purposive judgement because it tries to determine a concept and it is also with purpose, because it can successfully determine a concept for an object. While also being purposive, aesthetic judgement differs in that it is unable to ascribe a concept that would fit an object, so it is without a purpose.

An aesthetic judgement can be either a mere expression of liking or disliking in the sense of private taste, or it can claim universality – the difference of finding something beautiful and claiming that something is beautiful. On what grounds does Kant base this aesthetic objectivity?

To begin, he firstly claims that judgements of taste also always involve a relation to the understanding. [10] Understanding is that which imposes order. Similar to his four classes of logical forms, he examines aesthetic judgement by quality, quantity, elation and modality. Under relation, Kant states that beauty is defined as “the form of purposiveness in an object in so far as it is perceived apart from the presentation of a purpose. [11] He distinguishes between the form and the matter of purposive wholes and implies that form is given to everyone while matter is private to each. [12] Körner gives us an example of how a purposive whole can become a subject of both a teleological and aesthetic judgement and the difference between them. When observing a galloping horse, a teleological judgement of the horse would be an admiration of the harmonious interplay of its parts serving the broader purpose of the animal. But if we admire that same harmonious whole in a way that is detached from any purpose, we would be making an aesthetic judgement. [13] If an aesthetic object is a purposive whole without a purpose, it being purposive implies an imposition of order on what would otherwise be a mere manifold of perception. This imposition of order is the work of the faculty of Understanding. In the Critique of Pure Reason Kant explains how Understanding gives objectivity based on empirical judgements. He distinguishes between the given manifolds of perception, their collection by imagination and lastly the application of a Category which imposes an objective empirical reference. [14] Where an aesthetic judgement differs is that it does not involve the third feature, the application of a Category. In other words, it means that aesthetic judgement doesn’t refer an object to a concept, because of which our imagination is set in to free play when given the manifold of sensation. This is the source of the intellectual pleasure for Kant, the free play of imagination without constraining an object to a concept. In the example above, when observing the gallop of a horse without ascribing the concept of a horse to it, produces pleasure from an aesthetic judgement. In similar manner Körner observes the relation of such a judgement to a work of art by the phrase art for art’s sake – “ A work of art, whatever else it may be, is a self-contained entity, with a life of its own imposed by its own creator. It has internal order and external form, that by which we recognize it.” [15] Important to note is that when Kant talks about the interplay between imagination and understanding in the context of an aesthetic judgement, he is talking about a presentation of the object without the mediation of concepts. So in this sense understanding is implied as that which brings order and unity to the manifold of perception and not as something that ascribes concepts to objects.

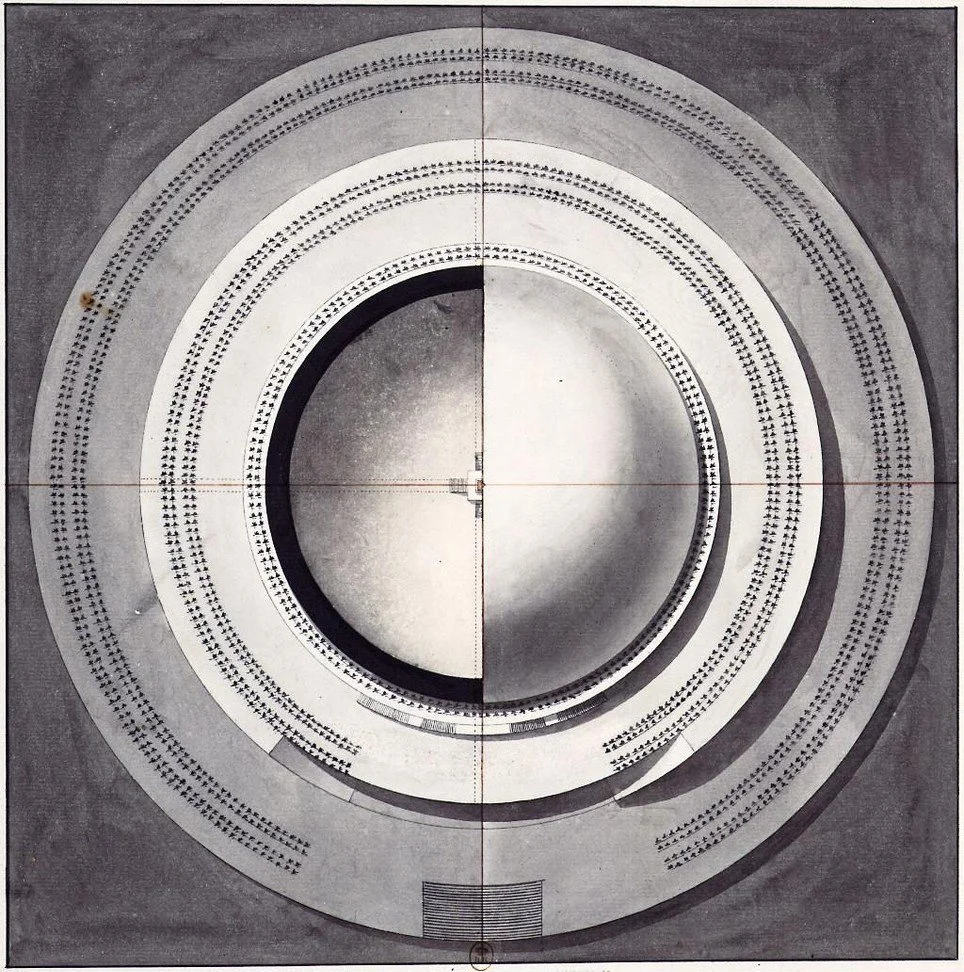

Étienne-Louis Boullée

Cénotaphe à Newton

1784

When talking about beauty in the context of “quality”, Kant describes taste as ”the ability to judge an object, or a way of presenting it, by means of a liking or disliking devoid of all interest. The object of such a liking is called beautiful”. [16] By interest Kant refers to the pleasure we get from the existence of an object, because in aesthetic appreciation we should be concerned with only the presentation of an object. Disinterestedness is a central concept to Kant’s theory on the aesthetics because it is closely tied to his claim that such a judgement is both subjective and universal. It is also the First Moment of aesthetic appreciation, one of the four unique features when making a judgement on the beautiful; the others being universality, purposiveness without purpose and necessity. He claims that beauty is indeed based on the sensation of pleasure but that pleasure has to be disinterested. It is important to note that in 18th century the word interesse meant a kind of pleasure that is neither grounded nor produces desire. For Kant there are two types of interest, that for the agreeable and the good, the lack of which distinguishes the beautiful from the other two. Since interest is related to desire, it can be said that it is also related to the existence of the object, in terms that one would want to take a possession of it. In aesthetic judgement however, the real existence of an object is irrelevant to the judgement itself. The judgements results in pleasure, as opposed to pleasure coming first and resulting in judgement. This is also closely related to Kant’s claim that the aesthetic judgement is concerned only with form of the object and not the sensible content, since content is connected to the agreeable through pleasure. For instance, Kant claims that the form of a poem may be studied as an end in itself – it is pure without any motives, and thus comes close to the aesthetic; whereas the content of the poem changes through time and context. As said previously, the form is given to everyone, but the matter is private to each.

When it comes to categorizing beauty, Kant makes a clear diction between free and dependant (or adherent) beauty, and subsequently two judgments of taste: pure judgements of taste that adhere to free beauty and impure judgements of taste that adhere to dependant beauty. Free beauty presupposes no concept of what the object ought to be, but is instead based on pleasure. While writing about aesthetic judgements in most of the Critique Kant is referring to free beauty. Dependant beauty according to Kant presupposes a concept of perfection against which to measure an object, it adheres to purposes that are external to the object. Dependant beauty starts to move its way in to concepts, it has some sort of criteria, a concept that regulates the beauty. Free beauty would for instance mainly be concerned with form, whereas dependant beauty would talk about morality, meaning, perfection, function or even its creator’s intention. When dependant beauty starts to form concepts such as decorum or “good” taste it moves from the realm of imagination in to the realm of understanding, understanding being for Kant a mental property that forms concepts. While understanding is interested in concepts, the aesthetic mental faculty is interested exclusively in feelings. Even though according to Kant, art is under the domain of dependant beauty, it would be wrong to suppose that it is valuable to us for the knowledge it provides us, instead it is to be valued for the pleasure it affords us. [17] It is important to note that this pleasure for Kant does not imply sensuous pleasure, but instead a pleasure derived from the free play of the faculties of imagination and understanding. In other words, in the case of free beauty, this free play results in cognition, whereas in dependant beauty it results in the experience of moral and practical values that are expressed in an aesthetic object [18], such as the moral value of a character in a portrait, or the functional qualities exhibited in a house. There is a contradiction in what Kant says about the aesthetic judgement of the beautiful when combined with his definition of dependant beauty: its reliance on concepts. The important distinction is when Kant says “Beauty is the form of finality of an object, so far as perceived in it apart from the presentation of an end”. [19] It would seem that in judgments of taste, beauty presupposes concepts such as an object’s end and perfection, but it does not presuppose the concept of the object itself. It is in the context of dependant beauty that connections can be made between Kant’s aesthetics and architecture. He claims that architecture, along with sculpture is one of the two plastic arts. Sculpture presents concepts corporally as they might appear in nature, but architecture presents concepts whose ground is not found in nature but in an arbitrary end. [20] Dependant beauty for Kant involves ends, for instance when he is referring to human beauty they would be moral ideals, similarly he mentions ends in the context of architecture, or more specifically residence. Kant says that in the beauty of residence “imagination has more freedom, almost as much as beauty that is quite at large, because the ends to which a residence may be put are not so clear as the moral ideal.” [21] If human beauty involves the representation of a moral ideal, it might be possible to conclude that for Kant a judgment of the dependant beauty of architecture might involve perceiving the visible expression of its end, such as dwelling.

Further on, the Second Moment is defined by aesthetic judgements behaving universally. What this means is that they expect an agreement from others, not that there is some objective criteria from which they come. To clarify, Kant is like Hume before him a subjectivist when it comes to positing the origin of taste between the subject and the object, however he makes a claim for a necessary universality in addition to subjectivity. His reasoning for this universality is two-fold. The notion that others ought to agree with our judgement of the beautiful firstly comes from a sensus communis or communal sense, noting how a sense of widely shared opinions gives a standard for an objective discussion of taste. He writes that “under the sensus communis we must include the idea of a communal sense, i.e. of a faculty of judgement, which in its reflection takes account (a priori) of the mode of representation of all other men in thought; in order as it were to compare its judgement with the collective Reason of humanity, and thus to escape the illusion arising from the private conditions that could be so easily taken for objective, which would injuriously affect the judgement”. [22] But even more important, universality in an aesthetic judgement according to Kant comes from the free play of our cognitive powers.

Kant gives an aesthetic judgement the same relevance to a cognitive judgement, but where they differ is how our cognitive faculties of imagination and understanding behave. Since an aesthetic judgement is a reflective judgement it presupposes concepts, and without concepts when assessing the beautiful, our imagination and understanding enter a state of free play – meaning they no longer only work together as in normal cognition, but further each other in a cascade of thought and feeling. According to Kant, “this state of free play of the cognitive powers, accompanying a presentation by which an object is given, must be universally communicable; for cognition, the determination of the object with which given presentations are to harmonize (in any subject whatever) is the only way of presenting that holds for everyone.” [23] The result of such a free play is disinterested pleasure, which is for Kant the basis for a judgement of taste. How I understand it is that when an aesthetic judgement of the beautiful is taking place, the cognitive process for every subject is essentially the same and this is what in Kant’s view gives such a judgement a property of universal communicability. Or in other words, since understanding and imagination are faculties that are required for cognition in general, they are a priori and therefore the same for all subjects. What is different in the aesthetic judgment is that they are released from the limitations of ordinary thought which enables the before mentioned free play. The conclusion is that Kant positions the aesthetic normativity in the shared faculties of human cognition. An interesting counterpoint would be, that this normativity could instead be positioned in the world itself, resulting in beauty being a given property in the world, which is characteristic to aesthetic realism.

To conclude, I would argue that beauty for Kant has a much more central position than one involving only aesthetic questions of taste, he tries to unify it to his theories of reason and morality. In Kant’s critique of theoretical reason he states that the causal relations between objects in the world are a product of the logical relations between concepts and categories in the mind. From my understanding the Critique of Judgement tries to implement this thought in relation to feeling and pleasure. In this, beauty for Kant acts in a way as a mediator between the natural world and human morality. When he makes a distinction between the phenomenal and the noumenal, he states that living organisms experience the phenomenal but are rooted in the noumenal. When we see beauty in nature it is as if a natural harmony is being established between our mental faculties and the organisation of the natural world. He speculates of a possibility between a natural world of appearances and the causal laws that determine them; and the inner world of moral freedom. In a teleological sense, Kant says that through our experience of purposiveness of organisms, our experience of beauty and the sublime infinitude of nature there is an undetectable unifying system that unifies the freedom of the human will and the determinism of nature. For him beauty is a passageway from the phenomenal in to the noumeal, and through the notion of beauty we can have some insight in to the unity between the freedom of the mind and the determinism of nature.

[1] Stephan Körner, Kant (London: Penguin Books, 1990), 176

[2] https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-judgment/

[3] Immanuel Kant and Nicholas Walker, Critique of Judgement, Oxford World’s Classics (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 179

[4] Stephan Körner, Kant (London: Penguin Books, 1990), 178

[5] Immanuel Kant et al., Critique of Pure Reason, 15. print, The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant, general ed.: Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood[...] (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 109

[6] Stephan Körner, Kant (London: Penguin Books, 1990), 178

[7] Immanuel Kant and Nicholas Walker, Critique of Judgement, Oxford World’s Classics (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 186

[8] Ibid., 211-212

[9] Ibid., 220

[10] Ibid., 203

[11] Ibid., 236

[12] Stephan Körner, Kant (London: Penguin Books, 1990), 184

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid., 185

[15] Stephan Körner, Kant (London: Penguin Books, 1990), 186

[16] Immanuel Kant and Nicholas Walker, Critique of Judgement, Oxford World’s Classics (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 211

[17] Robert Stecker, “Free Beauty, Dependent Beauty, and Art,” Journal of Aesthetic Education 21, no. 1 (1987): 90

[18] Ibid

[19] Immanuel Kant and Nicholas Walker, Critique of Judgement, Oxford World’s Classics (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008),80

[20] Ibid.,186

[21] Robert Stecker, “Free Beauty, Dependent Beauty, and Art,” Journal of Aesthetic Education 21, no. 1 (1987): 93

[22] Immanuel Kant and Nicholas Walker, Critique of Judgement, Oxford World’s Classics (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008),40

[23] Immanuel Kant and Nicholas Walker, Critique of Judgement, Oxford World’s Classics (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008),62